See listing of Recent and Most Popular articles on the Home Page

My World

Category: Holidays / Topics: Faith • Freedom • Government • History • Holidays • Inspiration • July 4 (U.S. Independence Day) • Politics • Values

Life, Liberty, and . . .

by Stu Johnson

Posted: July 4, 2016

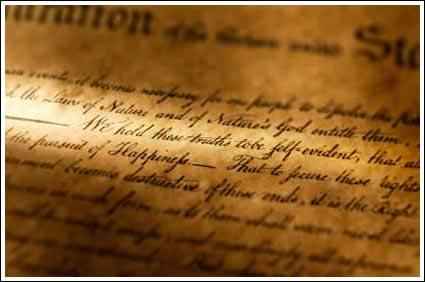

Is the Declaration of Independence a relic or a prized possession?

A not so happy celebration for some

Several weeks ago, a passing news story mentioned a woman who was suggesting that the Declaration of Independence should not be recited because it represents the establishment of a corrupt system of rule that persists to this day.

Such comments are not new, of course. They resonate with those who wish to opt out of reciting the Pledge of Allegiance, honoring the flag and other displays of patriotism to which they feel no obligation to support. Their argument may be philosophical or it may be deeply rooted in personal experience, living a nightmare of oppression, injustice, and lack of opportunity far removed from the “American dream.“

Years ago, a convention I attended each year was held in Washington, D.C. I looked forward to spending what free time there was exploring the National Mall. A visit to the Jefferson Memorial was particularly memorable. Practically alone, in the soft glow of a late-winter evening, there was time to reflect on the eloquent words carved in stone, seemingly for posterity. To me, the inscriptions were inspiring, demonstrating a deep faith in humanity, a benevolent Creator, and the ideals of self-rule.

Those words carved in stone represent the ideal, the blueprint as it were, for the great enterprise of an America that is still being fashioned more than two centuries later. Sadly, there are those who urge the removal of such words from public buildings, or in the extreme to tear down such memorials because, these critics feel, the words ring hollow, are vestiges of ideas that are no longer true (in their minds), or came from people who also embraced—or at least failed to abolish—the abhorrent practices and beliefs of our past.

I choose instead, to recognize that we all fall short—indeed, we can be blind to the problems of our own age, upon which we will be judged in the future—and we need the inspiration of ideas that elevate us, that motivate us to greater good.

Learning from history

Recently, I have been reading some of David McCullough’s masterful storytelling, from the Johnstown Flood, to the building of the Brooklyn Bridge and Panama Canal, and biographies of the Wright brothers and Teddy Roosevelt. All are engrossing tales of human nature and the American spirit. By sheer coincidence this July 4, I am currently reading McCullough’s biography of John Adams, which describes the fascinating story of America’s birth as an independent nation, as well as the inspiring story of the relationship between John and Abigail Adams, revealed principally in diaries and the letters written to each other.

The role of Abigail Adams, as well as other wives of “Founding Fathers,” is an interesting one. Typical of these strong and independent women, it was Abigail who urged John to see the need for the colonies to declare independence before he turned his own mind from loyal subject of the crown (or at least his commitment to fair legal representation of the king’s subjects) to a “true blue” supporter of independence. Abigail also urged John, in what appeared to become a running dialogue in their letters, to recognize the role that women should play in the new America, as well as the scourge of slavery. John called Abigail a “stateswoman,” and the melding of ideas between them is a fascinating story in its own right.

A better way to govern

John Adams, who had become a preeminent attorney widely known throughout New England, was a key person at a pivotal time in history. As David McCullough says, “For Adams the structure of government was a subject of passionate interest that raised fundamental questions about the realities of human nature, political power, and the good society.” Quoting from Adams’ essay Thoughts on Government, we get a sense of this unique person and his times:

I am more and more convinced that man is a dangerous creature, and that power whether vested in many or few is ever grasping. . .

It has been the will of Heaven that we should be thrown into existence at a period when the greatest philosophers and lawgivers of antiquity would have wished to live, a period when a coincidence of circumstances without example has afforded to thirteen colonies at once an opportunity of beginning government anew from the foundation and building as they choose. How few of the human race have ever had an opportunity of choosing a system of government for themselves and their children? How few have ever had anything more of choice in government than in climate?

While Thomas Jefferson was the masterful wordsmith of the Declaration of Independence, the stamp of John (and Abigail) Adams is seen throughout, including its most famous statement:

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights, that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. That to secure these rights, governments are instituted among men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed.

It is interesting to see how much more powerful these words became with numerous edits along the way. As McCullough points out, “To no one’s surprise, Adams [who served on the committee tp draft the Declaration] did not sit silently by. He was present every hour, ‘fighting fearlessly for every word,’ as Jefferson would write.” (While these few words are among the most famous, the majority of the Declaration is a listing of specific grievances against King George III and his treatment of the American colonies.)

Critics of the Declaration and the new government eventually put into place, point to the emptiness of the words “all men are created equal” when slavery was still a foundation of the economy of the southern colonies (with many in the north having their own dependence on it). Such a reading ignores the fierce debate that ensued in the Continental Congress and later in the Constitutional Convention.

The fight over slavery was very much a part of those formative debates, which is lost on many Americans, whose understanding of history is staggeringly appalling. The ideal of equality was strongly stated in that short statement, “all men are created equal.” Rather than seeing them as hypocritical, I would suggest that the words echo through our history, driving the eventual abolition of slavery nearly a century later and inspiring the civil rights movement that took hold still another century after that. Words of inspiration should not be dismissed because they do not reflect the contemporary reality; but because they represent a high standard that may take enormous effort to achieve.

The pursuit of happiness

The words “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness” in the Declaration of Independence have always intrigued me. “Life” and “liberty” are words of such weight and consequence, while “pursuit of happiness” seen 240 years later seems lightweight—little more than modern America’s adoration of materialism, celebrity and living in the moment. Yet, for Adams and his colleagues those words bore much deeper meaning, setting the stage for the freedom that allows the enjoyment of happiness in all its forms.

As McCullough explains,

The happiness of the people was the purpose of government, [Adams] wrote, and therefore the form of government was best which produced the greatest amount of happiness for the largest number. And since all “sober inquirers after truth” agreed that happiness derived from virtue, that form of government with virtue as its foundation was more likely than any other to promote the general happiness.

The link between virtue and happiness, and the impact on the shape of government, made me ask how that concept applies to business, or education, or health care, or religion, or marriage and family, or any of a host of other human institutions.

In business, is the focus solely on obtaining profit (the “power...ever grasping”), or is it balanced with the virtues of creating good work, demonstrating character, offering the highest quality product or service to the consumer at a fair price, contributing to the greater good in the process? In every institution, the concept of virtues should hold at bay the urge to focus on that which benefits a few, while the real purposes of that institution are diminished and the public ill served and even harmed.

Like a building, the integrity of a social institution relies on a firm foundation and strong framework—things largely unseen (call it character, or Adams’ virtues)—but without which the structure will buckle under stress or collapse of its own unsupported weight.

The question today is whether the dream expressed in the Declaration of Independence—and the long struggle that followed to win independence and establish a Constitution—is simply a footnote in history or the foundation of ideals uniquely stated in history and worthy of our concerted effort to pursue and protect for posterity.

Have a Happy Independence Day!

Search all articles by Stu Johnson

Stu Johnson is principal of Stuart Johnson & Associates, a communications consultancy in Wheaton, Illinois. He is publisher and editor of SeniorLifestyle, writes the InfoMatters blog on his own website and contributes articles for SeniorLifestyle. • Author bio (website*) • E-mail the author (moc.setaicossajs@uts*) • Author's website (personal or primary**)* For web-based email, you may need to copy and paste the address yourself.

** opens in a new tab or window. Close it to return here.

Posted: July 4, 2016 Accessed 604 times

![]() Go to the list of most recent My World Articles

Go to the list of most recent My World Articles

![]() Search My World (You can expand the search to the entire site)

Search My World (You can expand the search to the entire site)

![]() Go to the list of Most Recent and Most Popular Articles across the site (Home Page)

Go to the list of Most Recent and Most Popular Articles across the site (Home Page)

Loading requested view...

Loading requested view...